Criminally Overlooked: “To Live and Die in L.A.”

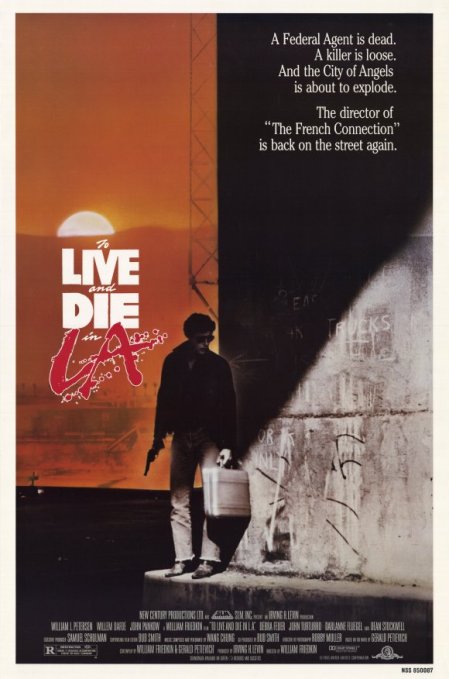

March 17, 2010The poster for To Live and Die in L.A. boasts “The director of the French Connection is back on the streets.” It’s a line that could set movie fans’ heart’s a-flutter. After all, Connection, beyond being possibly the best cops and robbers movie ever made (at least at the time), was also one of the seminal films of the 1970’s. And that’s probably part of the reason why TLaDiLA got plowed under at the box-office. Despite a plotline that seems to have been lifted from any number of Miami Vice episodes, and an edgy rock soundtrack, TLaDiLA is really a ‘70s movie in ‘80s movie clothing. Director William Friedkin turned his considerable talents and low-exposition/high-character-sketching style on a movie produced at the midpoint of a decade dedicated to movies that were bigger, dumber, and flashier. Never mind the fact that he produced something like a modern noir masterpiece. A few months earlier, Rambo: First Blood Part II had debuted. In its wake would follow Cobra, Commando, Action Jackson, and eventually Lethal Weapon. Audiences wanted explosions and not having to think. The movie never had a chance. But as you can probably imagine, I come here not to bury TLaDiLA, but to praise it as a movie which deserves better than it got.

The thumbnail description of TLaDiLA makes it sound like a clichéd pulpy throwaway. US Secret Service Agent Richard Chance (William Petersen) seeks revenge for the death of his partner. Teamed up with a hesitant rookie (John Pankow) Chance goes outside the law when the system refuses to let him get close to the counterfeiter (Willem Dafoe) who killed him. Standard stuff, sure. I mean, Chance’s partner was getting set to retire fer chrissakes! But, just as he did with Connection’s nab-the-big-drug-kingpin story, Friedkin shows that even the most threadbare of tropes can fuel a great movie—if the rest is done right.

First off, the characters and casting does a hell of a lot of heavy-lifting. Chance is more than the stereotypical “hotshot/loose cannon/loner/renegade.” He’s presented as a guy with both street smarts and a set of titanium-armored balls. In his first scene (which is totally unconnected to the rest of the movie) he disarms himself in an attempt to talk down a suicide bomber. In his next scene he’s bungee-jumping off a bridge. Later he’s shown sleeping with one of his informants (Darlanne Fluegel) in what we’re led to believe is a long-running info/sex arrangement. Chance is basically a guy who has never believed anything he does is wrong. His self-centricism is as much a motivating factor in his plan for revenge as grief over the death of his partner. Chance is pissed that the guy killed somebody he considered righteous and he’s doubly pissed his bosses won’t let him take the guy down (he’s never even shown grieving over the loss of his friend and partner). Even late in the game, when Chance’s outside-the-lines coloring begins to veer into the tragic, he barely registers the collateral damage that threatens to swallow him and his new partner.

As Chance, William Petersen practically swaggers off the screen. He plays the character as a dog chasing a rabbit. Armored by his badge, gun, fists, and wits, Chance cruises through every situation blind to everything but his own wants and needs. He ignores his snitch/sex-toy’s attempts at introspective conversation. When an AUSA doesn’t move quickly enough on a warrant he presents, Chance explodes, “If I was one of your asshole cronies, you’d be spread-eagled over your desk right now!” Petersen sells his every scene, though, and never plays Chance as a cliché or an archetype. As a result, Richard Chance is one of the most vivid characters ever to lead a crime movie. A year later Petersen would take a completely different route as the tentative Will Graham in Manhunter—a man who distrusts his own massive intelligence and the fragility of his psyche. After that, he was pretty much relegated to bit parts and walk-ons. That’s why I was so happy he conquered the TV world as Gil Grissom on CSI, and I was even happier when he ditched the show to do more exciting stuff. Petersen may be known to most people as “that guy from CSI,” but at least he’s known to most people.

To Live and Die in LA isn’t afraid to show Chance screw up, either. Whether it’s because his balls/brains ratio is off or because his increasingly desperate quest to take down Masters has made him sloppy is an open question for the viewer to contemplate. He loses a prisoner he’s flipped by falling for a ludicrously simple ruse. He willingly goes into buys without backup. He never once considers that his sex toy snitch might not being playing straight with him. It’s a mark of the movie’s maturity–and the trust it places in the audience–that it treats the good guy as anything but infallible.

As his nemesis, Rick Masters, a startlingly young Willem Dafoe plays the opposite end of the spectrum. Masters is deliberately opaque, despite his own flamboyant streak. He’s an artist on canvas as well as with currency. But Masters burns his paintings, while he sends his currency out into the world. His dancer girlfriend Bianca (Debra Feuer) is a willing accomplice in his criminal activities, and the two of them have a close, kinky relationship—at one point, Masters brings another woman (a very young, very pre-Fraisier Jane Leeves) home as a sexual plaything for Bianca while he’s out moving some funny-money.

But Masters is nothing if not a nihilist, matter-of-factly burning anything that might leave a trail to him as dispassionately as he burns his paintings and as dispassionately as he kills several characters in the course of the flick. He’s a great bad guy, because he matches Chance’s kicked-in-doors mentality with cool professionalism. Dafoe plays him with varying measures of sleaze, confidence, intelligence, and ruthlessness. He’s like the smartest, evilest lizard ever to wear a turtleneck, take in an avant-garde dance performance, and then insult someone’s taste in sculpture before shooting him in the face.

Against these heavy-hitters, it’s easy to lose track of John Pankow as John Vukovich, Chance’s rookie partner. Chance obviously considers Vukovich to be a weak suck, but he’s easily controlled and handy at times. But Vukovich is tormented by their increasing lawlessness, and by the end it’s even money whether he’ll follow Chance on his personal vendetta or take him down. Pankow underplays his role, but is totally unafraid to look soft, sad, and conflicted while everyone around him simply acts and never considers. He’s the moral center of the movie, and he makes morality look passive and useless.

Friedkin directs with the same naturalistic style he brought to Connection, but while the natural chaos of 1970s New York City filled the stylistic void, L.A.’s open spaces and low, flat expanses force a sense of contemplation on the film. The stakes and violence of the unfolding story play against this emptiness and seems infected by the same nihilism that infects Masters’ life. This, too, presents a strange sort of tension. When a quest for revenge ultimately seems small and impersonal, the audience senses that the outcome could go any direction at all.

This isn’t to say that the movie isn’t exciting. In the year when John Rambo killed fuck-tons of Vietnamese with a stolen gunship and then shot down another gunship, Friedkin deftly shows that less is more in a simple close-quarters fist-fight. But Friedkin is only setting us up. After a series of small-scale, intense action scenes, he closes the deal on Chance’s fate in an astounding car chase that goes from a barren train yard through empty reservoirs, and finally the wrong direction on the L.A. freeway. A decade before CGI could put any imaginable carnage on-screen, Friedkin gives us possibly the most breathtaking car chase ever filmed. It took six weeks and Christ-only-knows how many cars, but it stands as a monument to the craft of filmmaking.

The movie isn’t perfect. The reason Chance can’t get close to Masters—the Secret Service won’t authorize the amount of money he demands up front—seems like the kind of thing even an adrenaline addicted wrecking ball like Chance could get past on the level. And the Field Office’s nonchalance at refusing to investigate the murder of a fellow agent doesn’t quite track (this could be because the FBI would be tasked with investigating the death of a federal agent, but the movie never mentions this). Still, the movie pushes past these incongruities, and by the end you suspect that whatever happened differently in the meantime, the way it ends is the way it always would have ended.

It would be ten years before Michael Mann brought the craft of filmmaking back to the crime genre with Heat. Strangely enough, though, TLaDiLA stands tall beside it. While not a Michael Mann film, it has many of the same strengths. It presents an inside view of cops and criminals that cuts beyond most of the cops and robbers crap we’re treated to in the movies. It boasts solid performances, but no star turns, and never lets actors control the action. Finally, it shows what happens when you let genuine craftsmen—professionals—loose on simple, but compelling premise. You get a real, honest-to-God movie. Not a diversion. Not an entertainment. Something on the screen that’s engaging and interesting and thought-provoking, and something you haven’t seen before.

If you have never seen To Live and Die in L.A. go out and rent it. If you haven’t seen it and don’t rent it, I hope you get bitten by a snake (not a poisonous one–I can’t afford to lose the readership).

STUFF I DIDN’T GET AROUND TO:

–The pathos of the fact that Darlanne Fluegel’s character works in a strip club not as a dancer, but as a ticket-seller.

–The awesome Wang Chung soundtrack (that’s right: I used “awesome” and “Wang Chung” in the same sentence.)

–The hilarious capping line to the LAX chase scene.

–John Turturro

–Cool guns: S&W Model 19 .357 vs. H&K P9s .45

Oh, yeah. Terrific film, great car chase. Peterson’s character and performance nicely complex. Vukovich gets a chance to be more than a sidekick or foil. The book on which the movie is based is also quite good — as are the Petievich’s other books. Some yrs ago, a cop told me there were just a handful of writers who got it right: Higgins (say, The Friends of Eddie Coyle), Elmore Leonard (his earlier Detroit books), and Petievich.